Innovation and experimentation define Japan’s asparagus sector

Asparagus was first introduced to Japan by the Dutch during the Edo Period (1603-1868), but as with many exotic plants, it was initially grown as an ornamental rather than for eating. In the early 20th century, cultivation of white asparagus began in Hokkaido, mainly for export to the European market, although it was also served at a select few high-end French restaurants in Japan. It was not until the early 1970s that asparagus was widely cultivated for domestic consumption, with the green type dominating. Satoru Motoki of Meiji University treated attendees at the IAS 2022 conference in Cordoba (Spain) last June to an engaging talk about the Japanese asparagus sector and provided insights into the many research projects underway “to achieve high quality at each stage of asparagus production, marketing and consumption”. Asparagus has become one of the most popular vegetables in Japan and is widely cultivated across various regions of the country with green, white, purple and pink spears. While green asparagus remains the most popular among Japanese consumers, a recent trend towards diversification in dietary style has emerged, leading to an increase in the popularity of white asparagus. This trend has also driven a rise in cultivation area dedicated to purple and pink asparagus. The marketing of asparagus in Japan has become diverse in recent years, with consumers seeking uniqueness and variety. This has resulted in the marketing of different forms and sizes and the introduction of new kinds of asparagus, such as mini-asparagus, and three-colour sets of asparagus.

Rise of pink asparagus

The Japanese employ the different coloured asparagus in a variety of ways. Green asparagus is the most popular for eating in its fresh raw form. Besides being marketed in different colours, the asparagus spears also come in various lengths and shapes. As Western cuisine has become increasingly popular in recent decades, Japanese people have been drawn to white asparagus as something new and tasty to try. Similarly, the cultivation of purple asparagus for eating in its fresh form has also begun to increase. And it’s not only taste that counts in Japan. Aesthetics also plays a key role in the country’s cooking, which is part of the appeal of innovative pink asparagus, which has been gaining attention in recent time as consumers attach importance to uniqueness. Pink asparagus is prepared by shielding purple asparagus from light to make white asparagus, and subsequently applying light to it until it takes on a pink colouration.

New techniques emerging

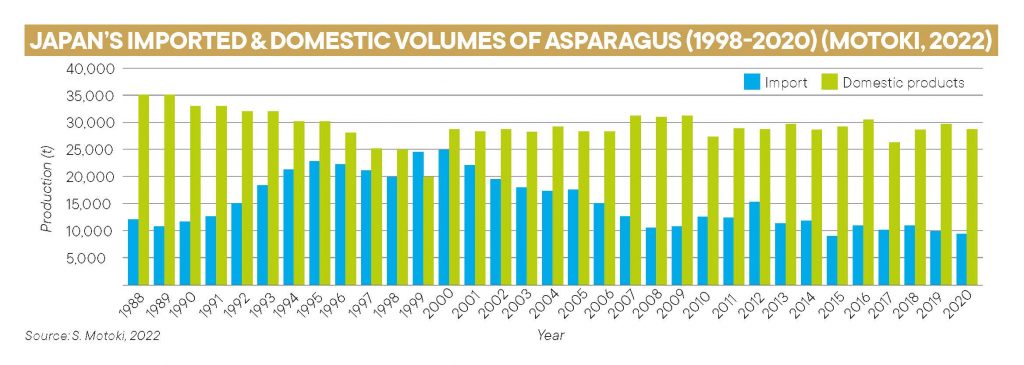

Meanwhile, domestic output has remained relatively unchanged for the past 26 years, averaging around 30,000 tons annually, ranking Japan 8th at the global level. Asparagus is grown in different parts of Japan to harness the full potential of its various climates. Hokkaido Prefecture is Japan’s largest asparagus producing region, where around 3,300 tons is grown on average each year. The other growing regions are Saga Prefecture (2,900 tons), Kumamoto Prefecture (2,100 tons) and Nagano Prefecture (2,100 tons) (Japanese Ministry of Agriculture, 2022). The climate in these prefectures ranges from subarctic to subtropical, allowing for the production of asparagus in a variety of cropping types.

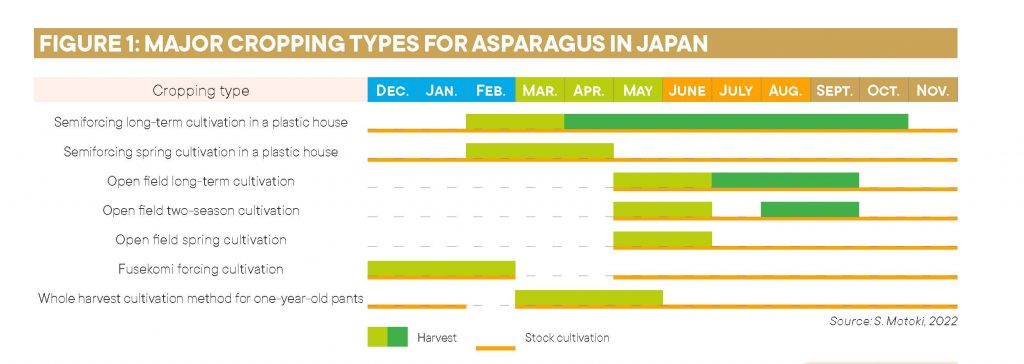

Hokkaido Prefecture has a climate similar to that prevailing in the northern part of the United States and Canada and in Northern Europe (Germany, the Netherlands, Poland, etc.), while Saga Prefecture and Kumamoto Prefecture have a climate resembling that along the western coast of the United States. Due to its high soil adaptability, asparagus is considered an excellent crop for growing in Japan’s upland fields that have been converted from paddy fields. To address the lack of off-season product, Japanese farmers have developed new techniques for year-round asparagus production. One technique that is spreading quickly is called fusekomi forcing culture, while another innovative method is the whole harvest cultivation method for one-year-old plants, which enables the cultivation of asparagus in larger quantities in a shorter period of time.

Fusekomi forcing culture

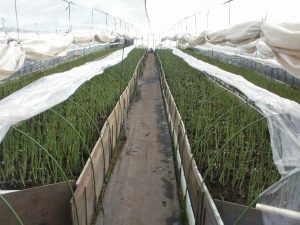

“Fusekomi forcing culture is a technique employed to be able to harvest asparagus during winter. Unique to Japan, production via this method is performed in part by using dug rootstocks,” said Motoki, and it plays a key role in the country’s asparagus production in the winter and early spring (December to March). The technique involves cultivating the asparagus rootstock for a short period of time (about 1-2 years) in an open field, digging it up in the autumn and planting it into beds arranged within a greenhouse, followed by warming until the spears are harvested. However, as Motoki pointed out, this approach “requires digging up the rootstock, which means that there is a need for specific farming machines and special skills. It is also necessary to have a special facility such as greenhouse in which the dug-up rootstock can be planted.”

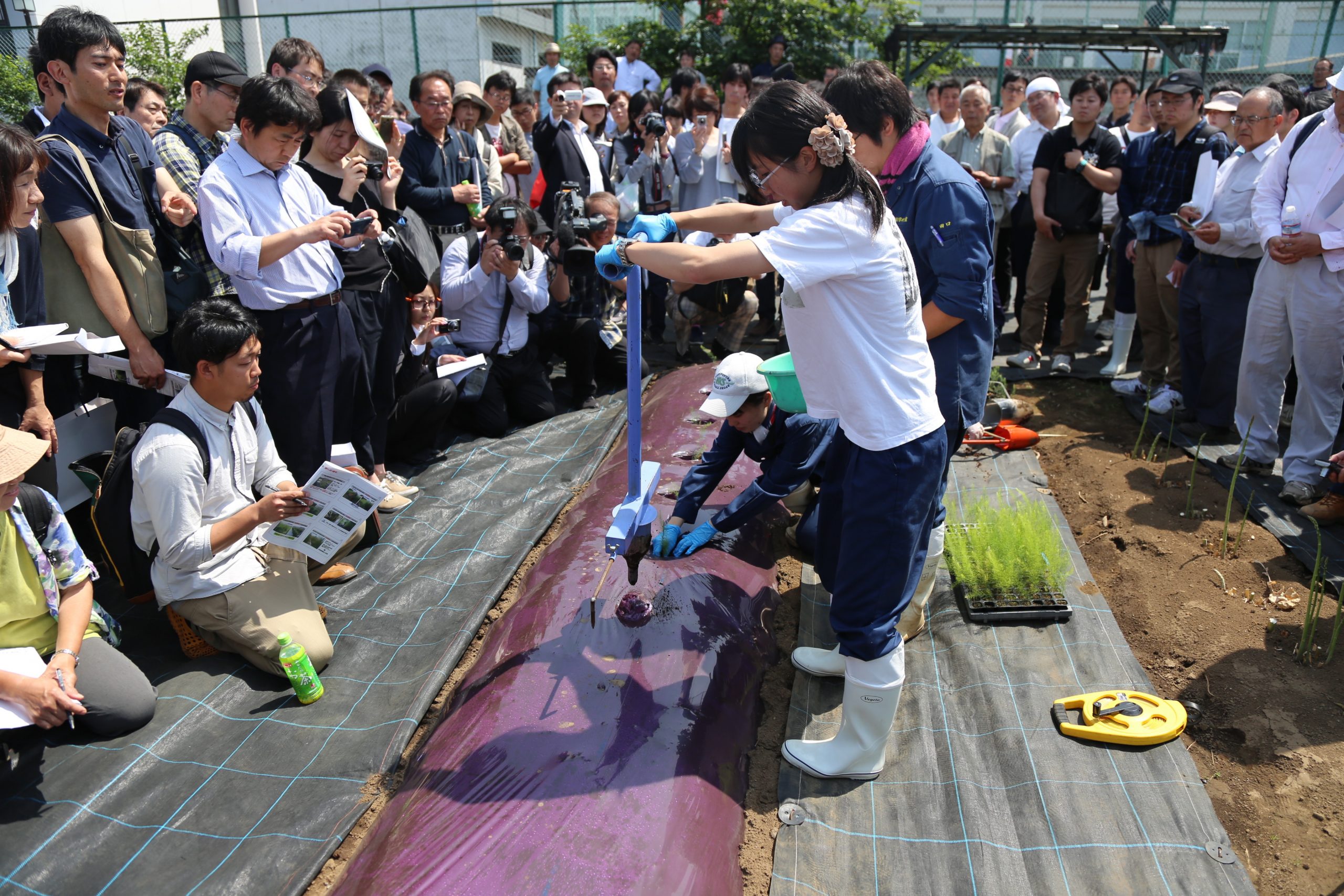

Whole harvest cultivation method for one-year-old plants

A simpler technique developed by Motoki and colleagues is the whole harvest cultivation method for one-year-old plants. One benefit offered by this method is its brevity, with the cultivation process completed within one year of planting the seedlings. Conventional cultivation techniques require several years before a stable yield can be established. “Another advantage of this technique is that it involves lower risk of disease and pest damage. Cultivation from thfe same plants over many years results in increased likelihood of such afflictions occurring each year,” said Motoki. What’s more, the whole harvest cultivation method for one-year-old plants can even be employed by beginners without too much training necessary. Launched in 2016, and the first of its kind in the world, this technique is currently spreading rapidly across Japan thanks to the combined efforts of the government, Japanese agricultural cooperatives (Zen-Noh) and private enterprises. The method has been the focus of multiple TV programmes and newspaper and magazine articles that have attracted growing attention. In the academic realm, since 2020, researchers at Meiji University have been studying cultivars/lines selection using the whole harvest cultivation method for one-year-old plants in cooperation with Walker Brothers, Inc. of the United States.

Reusing plant parts

Researchers in Japan have also been exploring ways to make production more sustainable and resource-efficient by employing the parts of the asparagus plant that are normally discarded, such as its cladophylls. Despite Japan’s production of cladophylls totalling approximately 130,000 tons per year, only a small fraction gets utilised, with the rest either going to waste or returned to the field. Studies have shown that the beneficial component rutin is most abundant in the cladophylls and in the storage root of asparagus plants, while another valuable component, protodioscin, is most abundant in the buds and underground parts. Therefore, all of these parts offer great potential as rich sources of nutrition. Were storage roots to be left in the ground, besides making use of their valuable properties, another upside would be that it avoids the need to dig them up and saves labour. However, it has been found that if the storage root remains in the soil at the time of replanting, a growth inhibitor leaks out of it. “One way to supress this growth-inhibitory activity is with the use of active carbon,” said Motoki. So there is certainly great potential in utilising parts such as cladophylls and storage roots as it offers the potential to reduce waste, provide greater nutrition and save labour.

As long as the current levels of demand for asparagus hold in Japan, it is likely that new techniques will continue to be developed for growing this healthy and delicious vegetable and new varieties proposed to attract an even wider customer base.